Memories on Stone

In addition to precious vital details of Bialystok’s ancestors, many a tombstone on Bagnowka Jewish Cemetery in Bialystok, Poland, offers a glimpse into the world of Jewish Bialystok from the turn of the 20th century until the onset of World War II and the Holocaust. This glimpse may feature provocative expressions of familial love and affection, words of condolence amidst loss or, at times, startling unexpected details. Visitors to this page will find a gallery of images and comments on some of these most touching and compelling details. This page will be updated weekly as documentation and inscriptional review progresses after Summer 2018 restoration efforts.

Forgetful Children. The last tombstone uplifted this August (2018) – by hand (!) by two longtime-friends and volunteers, Ali Flagler and Alia Degen, begins with a matter-of-fact (but sweet) statement from a(n adult?) child to her or his mother, acknowledging that forgetfulness might occur: “I erected this stone matzevah (tombstone) to remember the day of the passing of my precious mother, perfect, upright, proper and important and modest in all her deeds and ways …”

On another tombstone, a unique trilingual inscription (Hebrew, Yiddish, Russian) reveals that the epitaph’s author is a bit more concerned and forceful regarding forgetfulness. “Children, remember your father” reads the Yiddish command tucked between the Hebrew and Russian epitaphs. This command does occasionally occur in other inscriptions on this cemetery; some even punctuate it with an exclamation mark! Both perspectives, nevertheless, evoke reader reaction as they comment on the biblical command, “Honor your father and mother” (Exod. 20:12), and perhaps the timeless desire for remembrance.

T

The maskil Avraham Ber Got(t)lober. Each stone holds a story. In Section 1, just inside the cemetery’s main entrance, stands the matzevah of maskil (intellectual) Avraham Ber Hacohen Gotlober, an early advocate of the Haskalah (Enlightenment) in the Russian Empire. His epitaph reads:

Here lies Avraham Ber Hacohen Gotlober, a writer, poet and teacher, a great friend of writers in Hebrew and in Jewish [= Yiddish]. He was born in Starokonstantinov 18 Tevet 5571/1811 and he died in Bialystok 20 Iyar 5659/1899. תנצבה. [Yiddish:] Whose matzevah was erected [by] the Bialystoker Literary Circle in the year 1925.

Gotlober was a prolific writer, especially of poetry, whose travels and teaching took him from his birthplace of Starokonstantinov, Volhynia (now Ukraine) to eventually Bialystok, where he died, forgotten and in abject poverty. Perhaps such circumstances are why his matzevah was erected by the Bialystoker Literary Circle in 1925 as recorded in the addendum to his epitaph. In a 1929 photo of this society, esteemed journalist (and more) Pesach Kaplan can be seen (center, right). The question is: Why wait until 1925 to erect his matzevah? At present, I do not know the answer. For more on Gotlober, explore Bagnowka: A Modern Jewish Cemetery on the Russian Pale (iUniverse, 2017).

In the photo gallery below, Gotlober’s original matzevah can be seen in a 1925 photo, a wrought-iron fence surrounding it, a not uncommon feature on more affluent gravesites in this cemetery. In the next photo (2005), the state of Gotlober’s matzevah some eighty years later can be seen, forgotten and in abject poverty. The next photo (2015) depicts Gotlober’s matzevah as partially restored, lifted by hand, tripod and pulley system, thanks to the efforts of the German organization ASF with international students and local volunteers. The stone could not be set upon its base at that time because of its height and weight. In the final photo (2017), the matzevah is completely restored, uplifted and set in place, thanks to the use of mechanized equipment as employed by the current Bialystok Cemetery Restoration Project.

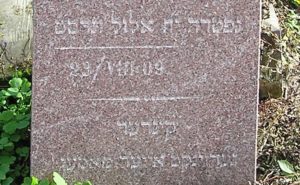

The wife of a maskil and daughter of a lumber magnate, Pelte Zabludowsky Halberstam. In Section 1, just inside the cemetery’s main entrance on Ul. Wschodnia, a section that holds the gravesites of some of Bialystok’s most distinguished Jewish residents, now stands the matzevah of Pelte Halberstam, fully restored in 2016. When I first encountered this tombstone in the early 2000s, I had no clue as to this woman’s identity, seeing only the sad fate of this matzevah, lying face down in the earth, like so many others on this cemetery. Only observable was its obverse inscription with her name Pelte Halberstam and the German/Yiddish “died” 20/1/1893. The base, however, still remained in-situ with its Hebrew inscription with her date of passing: She died at daylight Wednesday 15 Shevat 5653 [20 January 1893] about a year after this cemetery was established.

Some ten plus years of my waiting came to an end in 2015 when ASF and local volunteers turned over her tombstone and partially uplifted it. (Its weight and height were too much for the pulley-tripod system then in use.) Finally, I would learn more about this woman. What a revelation to learn that she was the daughter of lumber magnate and entrepreneur Izaak Zabludowsky (d. 1865), purportedly ‘Russia’s richest Jew’, and an advocate of modernity that changed the culture of Jewish Bialystok at the turn of the 20th century. Her husband was Eliezer Halberstam, who is credited with bringing the Haskalah (Enlightenment) to Bialystok at about this same time. (Both husband and father’s name are given equal prominence in her inscription!)

The extant historic record offered slightly more about her life. She was the oldest daughter of Izaak Zabludowsky’s first wife, with whom he had eleven children; her husband Eliezer was Izaak’s step-son from his third wife; her sister, Malka Reizel married textile giant Sender Bloch; and Bialystok historian A.S. Herszberg commented that she was “a skillful Jewish woman” in the home and assisted with her father’s textile business. But her tombstone also held an eight-line poem that surely must offer some comment on her life that conjoined the Bialystok trifecta of Zabludowsky-Bloch-Halberstam:

“While yet in her father’s house, during the days of her youth, / her hands did not restrain from the ways of his house / and she performed service all the days of her life. / She was known in the gates by virtue of the integrity of her ways. / She smelled the scent of the Fear of God, pure and refined. /

(With both) a heart and a hand willingly she supported the contrite. / She rejected vile language; she cared for that which is perfect. / Truth was in her heart; truth was upon her lips. /”

Couched in the parlance of traditional religious language, drawing on Proverb 31:10-31, Pelte’s inscription can be read both as a testimony to a Jewish woman’s traditional care of the household and also surreptitiously as a woman involved on cusp of societal changes. As the oldest daughter of eleven children with her mother, Izaak’s first wife, who would be raised by Izaak’s second and third wives, it made perfect sense that she was active in his household and renowned in the community for her efforts. But “the ways of his house” may also suggest involvement in his business activities. In the final lines, where she rejected ‘vile language’ and ‘truth was upon her lips’, perhaps Pelte was the mediator between the radical intellectual language of her husband and the traditional world of Jewish Bialystok now under fire by the forces of modernity!

(For more on the Zabludowsky tombstones on this cemetery, see my 2017 University of Bialystok conference paper. The Polish translation should be available in the University’s volume of conference proceedings.

Questions. Two stones for a daughter. Gitl Lipshitz, d. 1899. At the front of Section 1, just inside the main entrance to Bagnowka Jewish Cemetery in Bialystok, Poland, are two tombstones for one young woman, Gitla b. Baruch Lipshicz (1878-1899). One now stands tall, respectfully restored in 2016 by the Bialystok Cemetery Restoration Project. The other lies beside it, its top fractured and gone, its center damaged irretrievably by the force of some weaponry. That the original was damaged is sadly not the surprise. Other tombstones in Sections 1 and 2 have also been violated by the effects of weaponry, as visible, for example, on the tombstones of Rochel Hinda b. Moshe Hatskles (c. 1920); Grona Cukerman (c. 1900); and Avraham Gershon b. Yaakov Sapiszinski (c. 1905), which also bears the graffiti letters KCL, the significance of which I have failed to learn. Clearly, Gitla’s tombstone was victimized after her passing in 1899, but when and by whom?

Gitla’s coming-of-age was at a time when the Bund labor party was on the rise; the Bund attracted young women as an alternative to a traditional Jewish life. Daughters, however, were often ostracized by family so perhaps her tombstone was vandalized as an attempt to remove her memory. This setting makes for a tantalizing historical drama like that of the Bundist Ester Riskind, of whom I have written in my book, Bagnowka: A Modern Jewish Cemetery o the Russian Pale. But nothing in Gitla’s inscription suggests her participation. The grief expressed by her father’s words suggests no such distancing from his daughter. Gitla was the sunshine that brightened his life.

While devastation clearly occurred on this cemetery during WWII and afterwards under Communism, I cannot imagine that the small number of Jews, who did survive the Holocaust and returned to Bialystok, had the time or funds to replace one tombstone amidst a devastated city. So, perhaps, the earlier events of WWI or the Polish-Soviet War are the catalyst for its damage. The timing makes sense. Her father or other family members would still be alive to replace the damaged, soft sandstone tombstone with a hardier granite one. Still how is it that one tombstone, albeit at the front of this section and not far from the southern wall, was hit by random fire and no others? Mere chance? And was there even fighting in this area?

And … two substantially different details were also incorporated on the new stone. The old stone ended: “She was gathered to her people on 12 Kislev.” The new records: “She was gathered to her people in a good rich name on 12 Kislev.” To be gathered in a good name, i.e. with a good reputation, is frequently found in epitaphs. The addition of the word for ‘rich’ is unique. It does not signify financial richness but derives from the word “olive oil; fatness” and signifies a rich viscosity or the plumpest morsel. But why later emphasize the quality of her reputation? This why remains the stuff of more historical imaginings.

The other difference, the old inscription ended with NO clear year of death but rather what is suggested is a chronogram, several words whose letters numerically add up to the date of death (“to the year of day of the death from the day of his [sic] birth according to the abbreviated era”). The letters to be added are typically indicated by diacritical marks; here they are not easily discernible! The chronogram is followed by the final blessing (“May her soul be bound in the eternal bond of life”), found on nearly all tombstones on this cemetery. The new ending simply indicates the year of death after this awkward statement and omits the final blessing. Yet why replace the literary intrigue of a chronogram? And why omit that final nearly universal closing blessing?

Ultimately, the biggest ‘why’ also remains. When such attention was given to replacing a damaged stone and adjusting these details, why not remove the old tombstone when the new was erected?!

Her epitaph reads:

A stone of darkness and the shadow of death.

[H] Howl with [B] weeping, [T] grief [W] and mourning, [L] for I am indeed [H] devastated!

[G] This heap is a witness because on (this) cursed day, exceedingly great is my pain.

[Y] Today my daughter was taken from me. Better had my soul been crushed!

[T] Before God she was called and her life is engraved upon my heart like a seal.

[L] To dust she returned and she forsook me; I will water your ashes with my tears;

[BT] Oh daughter, my eye grows dim from my affliction;

and from the intensity of my grief, I have dug out my pit;

[B] During the days of your childhood since the day you were born your sunshine brightened me.

[R] My appearance is your witness as is your corpse, and your lips [too] are a testimony of grief and moaning

[W] amidst desolate days in the days of your youth.

Your sunshine comes at noontime,

[K] surrounding my eyes waiting until I come to you to the clouds of heaven.

The young unmarried woman Gitl, daughter of Baruch Lipshicz. She was born 3rd Tishri according to the reckoning of mankind to receive their blood, whose days are like a passing shadow, 5639 [18 September 1878] and she was gathered unto her people in a good rich name 12 Kislev in the year and day of the death from the day of his [sic] birth 5660 [2 November 1899].